The leitmotif of my life

Rudolf Buchbinder on his project "Diabelli 2020"

No composer has been by my side as intensively as Ludwig van Beethoven, and none of his works has become a leitmotif of my life as much as his Diabelli Variations. Sixty years ago, my piano teacher Bruno Seidlhofer gave me, his youngest student at the Vienna Academy of Music, whom he liked to call "Burli" ("little chap"), the sheet music: "To my dear Rudolf Buchbinder with best wishes for the future" he wrote with ballpoint pen on the front page - Beethoven's "last waltz" has been with me ever since.

It was also Seidlhofer who let me play the first 25 of the total of 50 variations of the so-called "Vaterländischer Künstlerverein" in a student concert, variations by Beethoven's contemporaries who had also taken up Diabelli's waltz theme. Among them were Beethoven pupil Carl Czerny, his 11-year-old pupil Franz Liszt, Czerny's teacher Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Mozart's son Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart and Franz Schubert, whose C minor variation must have appeared otherworldly even to listeners at that time.

When I went to the Berlin Teldec Studios in 1973 to record Beethoven's Diabelli Variations for the first time, it was a matter of course for me to also record the variations of his contemporaries. After all, their pieces were a musical walk through Beethoven's Vienna. When I resumed the cycle just three years later, some colleagues had already given me the nickname "Monsieur Diabelli". In 2007, I was very keen to contribute with a charity concert and help the Beethoven Haus in Bonn acquire autographs of this piece. A document that provides us a glimpse of Beethoven's meticulous working process: from unreadable attacks of rage to meticulous corrections. Black, green and red ink and pencils - music that Beethoven partially scratched into the paper.

And indeed to this day, the Diabelli Variations remain one of my most frequently performed pieces. My uncle, who recognized and nurtured my musical talent at an early age, noted down my performances in a black ring binder, a habit I continued out of curiosity after his death. That's how I know that I performed the Diabelli cycle in public exactly 99 times before the Beethoven anniversary in 2020. "Diabelli 2020" is therefore also a private anniversary for me and my relationship with Beethoven.

It was only natural that I would want to take up the variation cycle again in the anniversary year, as well as my favorite variations by the other 50 composers. They form the chamber music contrast to my recordings of the anniversary piano concertos with Andris Nelsons and the Gewandhaus Orchestra, Mariss Jansons and the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Valery Gergiev and the Munich Philharmonic, Christian Thielemann and the Staatskapelle Dresden and with Riccardo Muti and the Vienna Philharmonic.

Anton Diabelli was not only a publisher, but also a very shrewd businessman. The book with the 50 printed variations on his waltz were something like the charts of his time, works of musical superstars that could be played in the salons. An ingenious marketing strategy, which Beethoven, however, avoided. This was due on the one hand to the number of his 33 variations, which exceeded all bounds, and on the other hand to their (at that time) sheer unplayability! It was not until 30 years after its publication that op. 120 was performed for the first time by the pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow, and even after that the Diabelli Variations, which Bülow called a "microcosm of Beethoven's genius", continued to have a difficult time.

For me, the Diabelli Variations are perhaps Beethoven's most exciting work. They are music about music. Beethoven was evidently inspired by Bach's "Goldberg Variations", but also quotes other "gods" such as Haydn or Mozart, to whom he dedicates the 22nd variation with the "Don Giovanni" motif. At the end, Beethoven returns to himself, quoting his last sonata, op.111, in the 33rd variation, and revealing his genius by dismantling a simple waltz into its structural parts in order to reassemble them in all their complexity in his own image. You could also say: Beethoven eats Diabelli's waltz and digests it before our ears.

That alone would be remarkable; what is ultimately a stroke of genius is that Beethoven does not conduct this process for the sake of the process, but rather uses the stages of the individual variations to raise a compendium of fundamental human questions and, on the basis of the variations, to explore the diversity of human nature. Beethoven places each element of the Diabelli waltz against the light of music history and conscientiously assigns it to the ideal of his present. For me, the 33rd variation enters a state in which my associations about Beethoven, about playing the piano and the Diabelli Variations also fade away into other realms.

It was clear to me: My "Diabelli 2020" project was going to bridge the gap of time, and a new recording of the Diabelli cycle would only make sense if contemporary composers were also asked to contribute a variation on the waltz. Of course, today we no longer think regionally or nationally like Diabelli, but we know that by 2020 Beethoven has long since arrived in our global world.

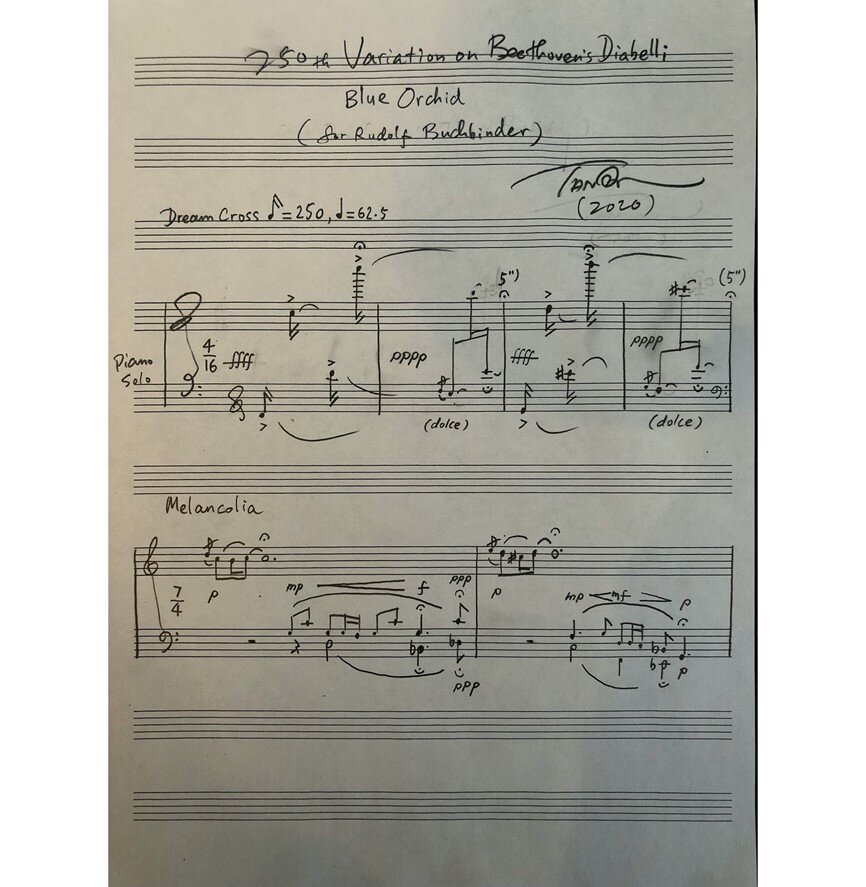

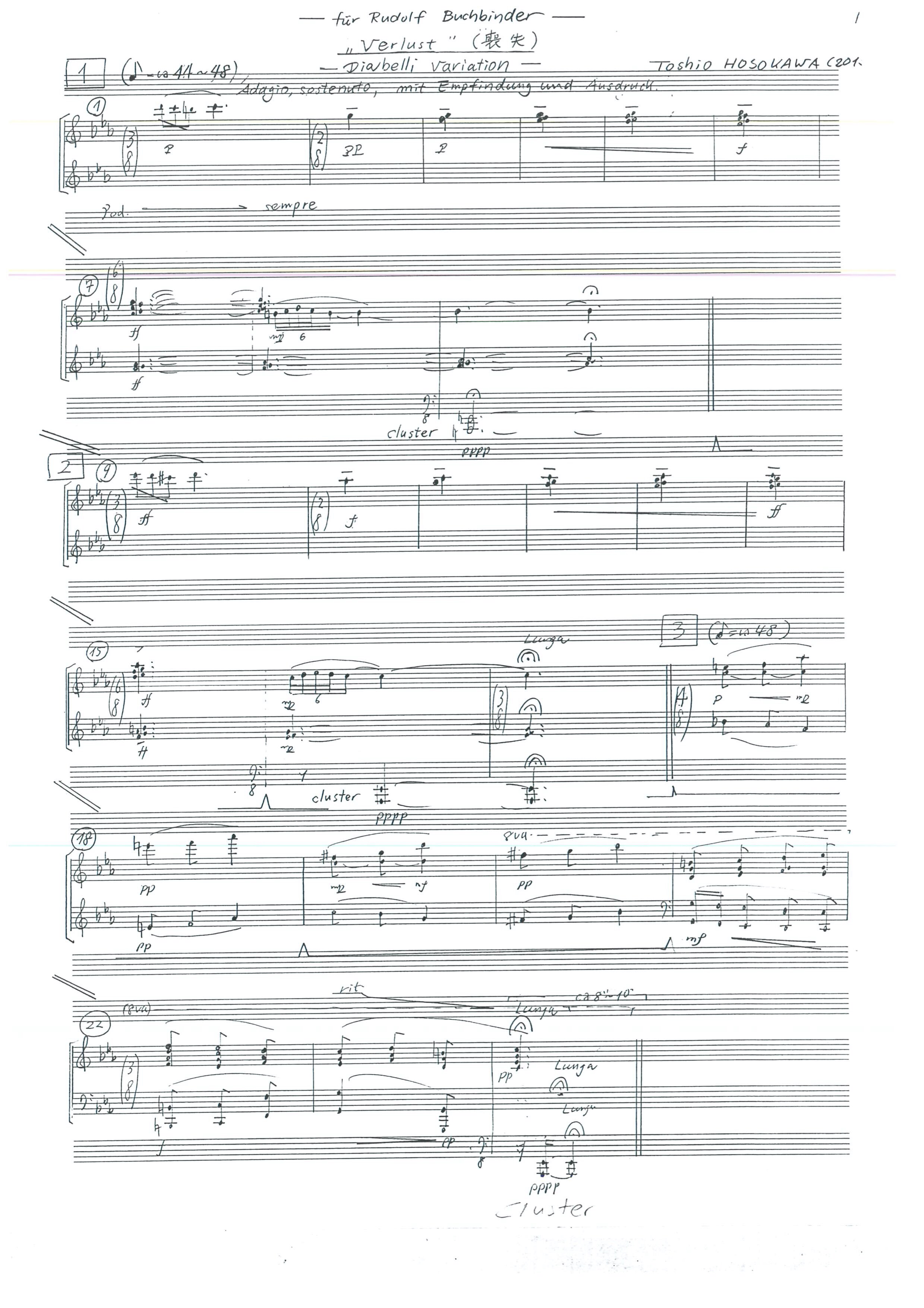

I am proud of the range of composers involved in this project: from the wonderful Lera Auerbach to Max Richter. I am also delighted that Tan Dun is taking part, whom I, as a cineaste, naturally admire for his Oscar-winning music to Ang Lee's cinema classic "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon". Toshio Hosokawa, probably Japan's most important contemporary composer, presented me with his score after a concert in Japan: Japanese characters written in pencil on the title page.

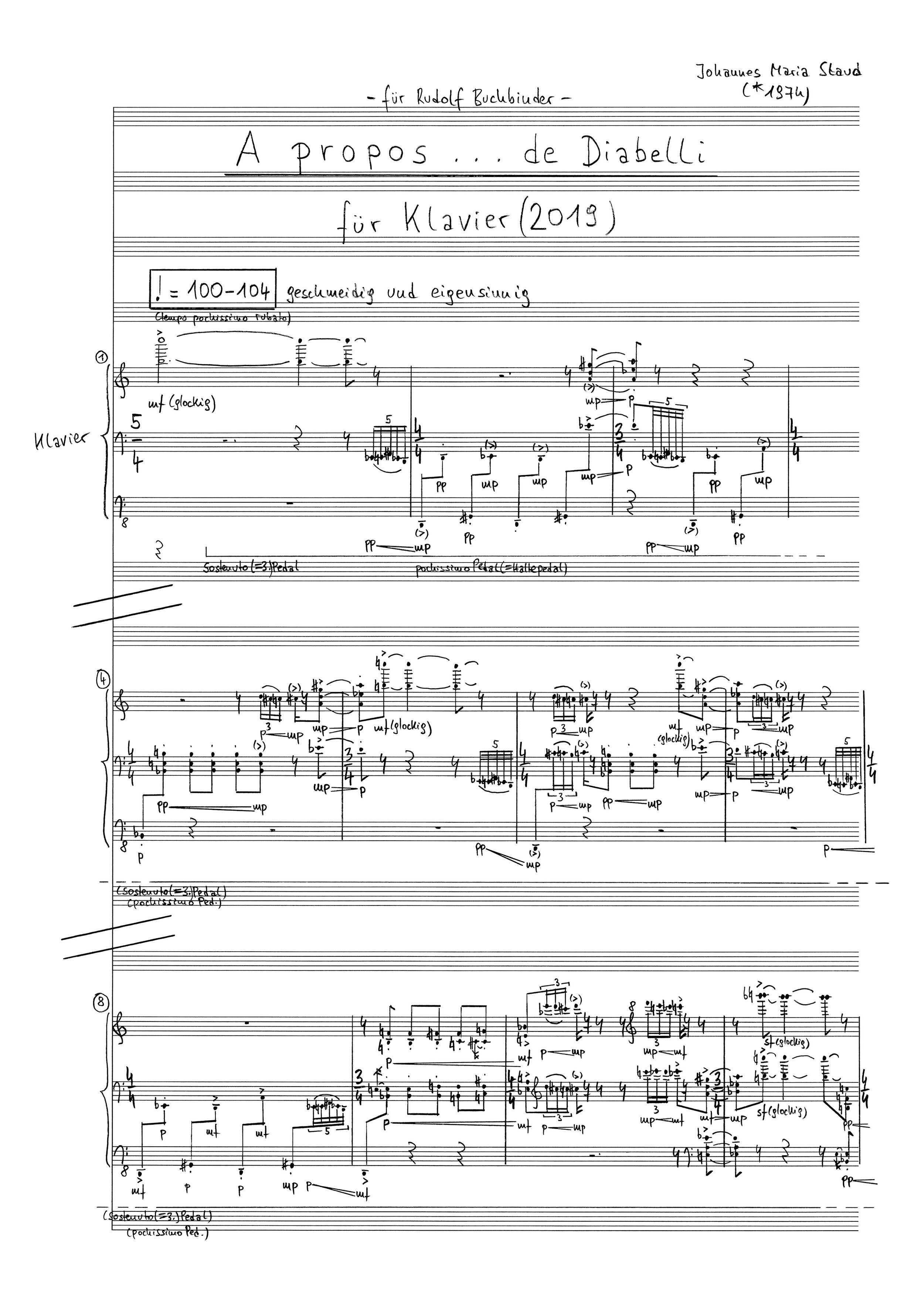

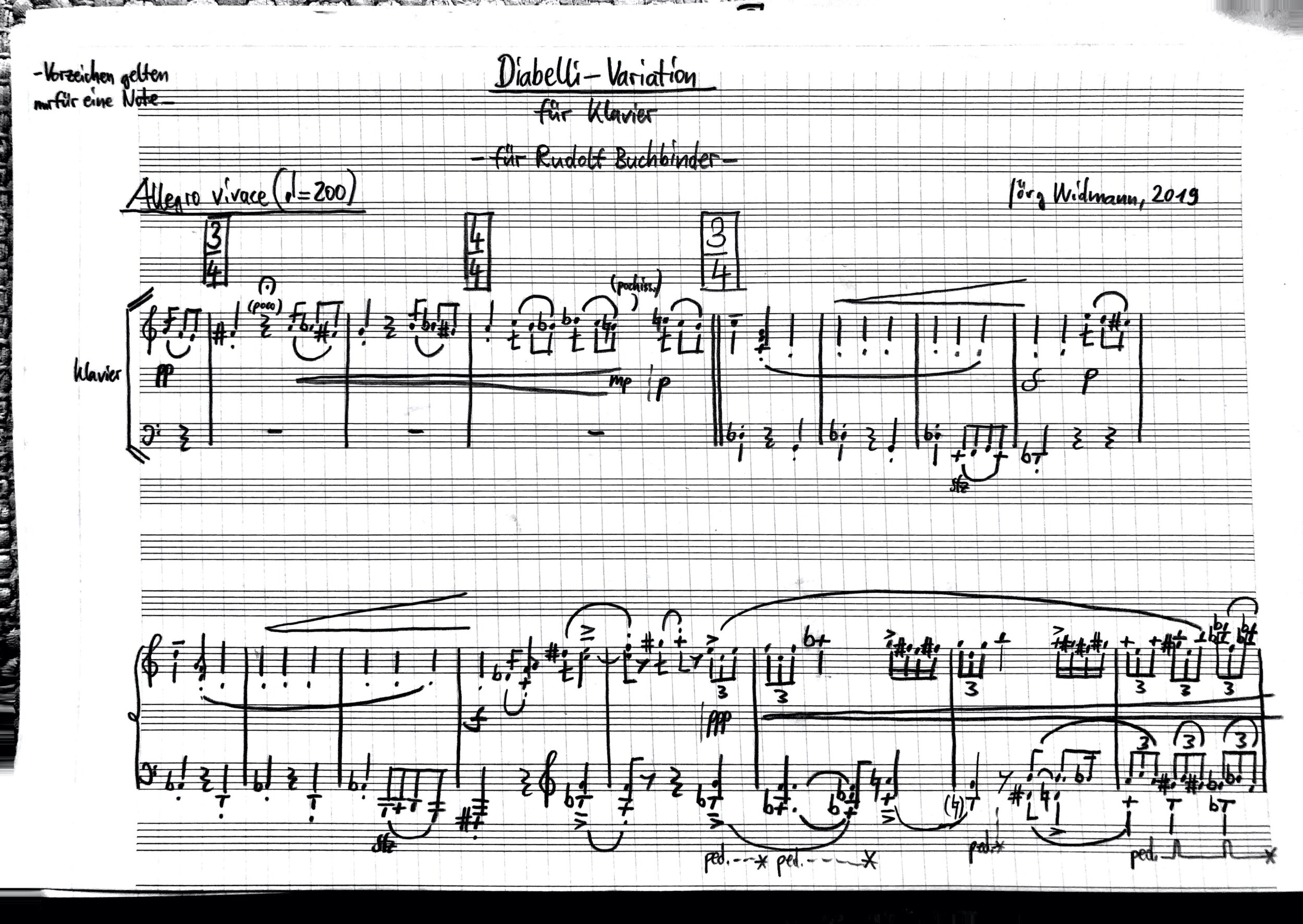

The Australian Brett Dean wrote his variation, and this is a great honor for me, "for RB in Admiration" and opens with a crazy "con fuoco", Toshio Hosokawa christened his work "Loss" and begins with an "Adagio sostenuto", and then - as is his trademark - strolls through Diabelli's soundscapes with Japanese serenity. No matter how casually the Austrian composer Johannes Maria Staud titled his variation "A propos...de Diabelli" and asked the performer to play "smoothly and obstinately", he certainly challenged me with his extremely creative notation. For the German conductor and composer Christian Jost, on the other hand, Diabelli's waltz is an inspiration for a joyful performance, as can be seen from the title "Rock it, Rudi!", which really did inspire me while practicing. Brad Lubman also traces an arc through music history in his "Variation for RB", as does the French composer Philippe Manoury, who programmatically calls his piece "Two Centuries Later" and sets the stage for the metronome (a tool that became popular in Beethoven's time). He notates no less than 12 different metronome markings. The Russian composer Rodion Shchedrin begins his variation "quasi improvisato", and the composer and clarinetist Jörg Widmann explores characteristic Beethoven traits in his detailed and multi-part variation - I was particularly delighted when I found the subheading "Boogie Woogie", because this is music I also like to associate with Beethoven.

I am often asked what goes on in my mind when I play a work like the Diabelli Variations. My answer is simple: not a lot! The process of thinking about and engaging with Beethoven must be completed long before the first note is played. During a concert, Beethoven invites the pianist to allow himself to drift. I don’t mean swimming aimlessly on the waves of sound. To let oneself drift with Beethoven requires knowing where one is at all times, knowing the musical navigation, the starry sky, the winds and the compass points of Beethoven's cosmos.

Anyone who has studied Beethoven's piano music intensively knows that Beethoven knew us pianists alarmingly well, our weaknesses and impatience when it comes to achieving quick effects, taking the tempo into our own hands, or impressing the audience with idiosyncratic dynamic design. Let's take the 10th variation: It begins with the words "sempre staccato, ma leggiermente". So Beethoven wants to hear a light-footed staccato. With the dynamic "pp", i.e. pianissimo, he describes the nothing from which this variation originates. Only eight bars later he already seems to no longer trust us. This is the only way to explain why he raises his finger and writes in the score again: "sempre staccato e pianissimo". As Beethoven has not provided any new dynamic markings up to this point, it should actually go without saying that we are still in pianissimo in the eighth bar. But Beethoven suspects that the speed of the variation, coupled with the staccato, might seduce us to become louder. He could have written: "Dear piano player, even if you would like to get louder here, pull yourself together and stay in pianissimo a little bit longer!"

All of this is only revealed when you compare the individual editions, because quite absurdly, some publishers have eliminated these duplications from the print as errors. It is important to keep close to Beethoven's original text. Because the more one is prepared to bend one's own will to the will of the composer, the more certain it is that one will hit the note Beethoven intended. To make a long story short: It’s too late to start thinking just before you play the first note of the Diabelli Variations. In the moment of the concert, it is all about trusting Beethoven and allowing yourself to drift on the enormous creativity of his variations.

(Recorded by Axel Brüggemann)

More from Rudolf Buchbinder about Anton Diabelli, Ludwig van Beethoven and playing the piano in his new book "Der letzte Walzer", published by Amalthea.